David Hirsch remembers how far away from civilization his property, located in the mountains above Fort Ross, seemed when he bought it in 1978.

“Things were pretty remote,” the grower/vintner, now 68, says. “To get to my place, you had to go through five cattle gates on dirt roads.”

The paved county road ended six miles away, which meant Hirsch had to travel that far to get to his mailbox. Except for a few sheep farmers whose ancestors had settled the hills in the 19th century, Hirsch was one of the few to live in the isolated region.

Another was Daniel Schoenfeld, owner of Wild Hog Vineyard, now 62.

Schoenfeld says he was “part of that back-to-the-land hippie movement of the 1970s. You think it’s rural now? You should have seen it then.”

The area isn’t far from the mountain settlement of Cazadero, the rainiest spot in California and just a few miles from the Russian River town of Guerneville. But the twisting, steep roads—old logging trails, often blocked by trees felled during massive winter storms—make getting around challenging, to say the least.

The scattered dwellings may be tough places for people to live, an hour or more from modern conveniences like supermarkets. But grapevines thrive on the high ridges of these coastal hills.

It’s the resulting wines, mainly Pinot Noir and Chardonnay and, to some degree, Syrah, that have made far northwestern Sonoma County so important, so fast.

Overall, the wines are distinguished by structural components that marry taut acids to sometimes angular tannins, rather than by specific aromas or flavors. The wines that possess a sinewy side can be difficult to appreciate when young, but often soften and deepen within several years.

Earth, Wind and Water

The federal government recognized the Fort Ross-Seaview American Viticultural Area (AVA) in January 2012, after a contentious scrum over political boundaries.

At 27,500 acres, it’s medium-sized by California standards, but only 555 acres are planted to grapes, according to the area’s unofficial historian, Linda Schwartz.

Schwartz and her husband, Lester, both 68, own Fort Ross Vineyard. She’s biased, of course, but she deems Fort Ross-Seaview “a very sweet spot to grow grapes.”

Most vineyards are located at more than 1,200 feet above sea level (the AVA boundary is at 920 feet) on the first two coastal ridges, or on the south- and west-facing slope of the third.

That largely puts the vines above the clutches of the incessant fog bank that blankets the beaches and the coast road in dank and chill during the growing season.

“I can see the fog below me on most days, although I can certainly feel the moisture,” says Donnie Schatzberg, 66, who bought his land in 1973. Now called Precious Mountain Vineyard, it sits at around 1,500 feet. Up on the ridges, daytime highs can get quite warm during summer. However, the heat is tempered by the prevailing winds that sweep in off the Pacific, which doesn’t exceed a chilly 60˚F, even in summer.

The result, says Jayson Pahlmeyer, the Napa vintner who bought his Wayfarer Farm Vineyard in 2000, is “just what you want to grow great Burgundian fruit: A warm spot in an otherwise cool area.”

This climate gives the wines structure. While Fort Ross wines may lack the immediately appealing fat of their Russian River Valley counterparts, they will generally age better.

“The tannins out there are young, angular and awkward in youth,” says Williams Selyem’s winemaker, Bob Cabral, who buys fruit from the Hirsch and Precious Mountain vineyards. “They take awhile to become rich.”

If elevation and maritime influence are two keys to the region’s success, a third, soil type, is more difficult to analyze. Because of the ever-shifting San Andreas Fault, soil composition differs greatly throughout the appellation.

Despite the propensity for monster rainstorms, the vineyards are well drained. Ehren Jordan, of Failla Wines, calls his dirt “rainforest desert.”

A Punctuated History

The viticultural history of the area is both old and new. The first grapes planted in Sonoma County—or in Napa, for that matter—were installed just east of the beach by Russian explorers in 1817, whose wooden military installation gave Fort Ross its name. (U.S. postal authorities first recorded the settlement of Sea View in 1883. Almost nothing remains of it.)

The viticultural history of the area is both old and new. The first grapes planted in Sonoma County—or in Napa, for that matter—were installed just east of the beach by Russian explorers in 1817, whose wooden military installation gave Fort Ross its name. (U.S. postal authorities first recorded the settlement of Sea View in 1883. Almost nothing remains of it.)

The Russians’ grapevines (as well as wheat and other crops) failed in the cold, damp weather. Frequent mudslides and rockslides often tore out the crops. The frustrated Russians eventually gave up their colonial aspirations and retreated to Alaska.

That was end of viticulture in Fort Ross for nearly 150 years. The first person to plant grapes in modern times, Mick Bohan, was a sheep rancher whose family originally had settled the high meadows in the 1870s, after loggers had stripped the land of old-growth redwoods.

In 1973, with the collapse of the sheep market, Bohan was desperate to make a living. He planted Zinfandel, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Riesling on the advice of an oenologist friend.

But Bohan never developed a brand or realized a vision for the region. That was left to a younger generation, the back-to-the-landers like Hirsch, Schoenfeld and Schatzberg.

Getting Crowded

The turning point in Fort Ross’s fortunes may have occurred in 1994.

“That was the year Kistler, Williams Selyem and Littorai all showed up [to buy our fruit],” Hirsch says.

At about the same time, Schatzberg, at Precious Mountain, offered some grapes to Williams Selyem’s winemaker, Burt Williams.

“He was out here the next day,” Schatzberg says. The two struck a deal that’s been honored to this day by Williams’ successor, Cabral.

With influential wineries identifying the vineyard names on the labels, critics took notice, as did wealthy winery owners from Napa and Sonoma who sought entry to the new golden region.

No longer was Fort Ross the Eden of off-the-gridders. The skies began to drone with helicopters carrying investors looking for cleared ridge tops to establish vineyards.

Jayson Pahlmeyer, Sir Peter Michael and Dave Del Dotto arrived, bringing new standards of viticulture to the region.

Jordan says he couldn’t help but notice the flotilla of bulldozers and backhoes that inched up to Sir Peter’s property.

“But, to me, there’s an older, funky way of doing things,” Jordan says, “and I wonder if it’s not better.”

Fort Ross’s new popularity is not for everyone. I was driving through the area one winter day and was stopped when a fallen tree blocked the road. A chainsaw-wielding guy with a long beard and hair below his shoulders was cutting the tree into pieces.

He was on contract with the county, he said, to keep the roads clear. He’d been living in the area since the 1960s, but was moving to Alaska. When asked why, he grunted, “Gettin’ too crowded.”

Still Underappreciated

Compared to larger areas that specialize in Pinot Noir, like the Russian River Valley and the Santa Maria Valley, Fort Ross-Seaview will never be more than a bit player in terms of quantity. But quality-wise, it has achieved a premier position.

Despite this success, consumers interested in exploring these wines will have to learn the players and vineyards by heart. It’s still not clear whether many wineries will use the new appellation on their labels starting with the 2012 vintage. Some may opt to stick with the more recognized Sonoma Coast AVA.

As Cabral says, “Unfortunately, once you travel out of Northern California, there are still people who think Sonoma is part of Napa.”

Failla Wines

Failla Wines

Ehren Jordan was a “jack of all trades” at Napa Valley’s Turley Wine Cellars in 1995 (he’s now director of winemaking). Proprietor Larry Turley’s sister, Helen, had a winery, Marcassin, in the Fort Ross area.

“I’d tasted a lot of Burgundy,” Jordan says, “and after tasting Marcassin’s ’94 [Pinot Noir], I thought, ‘I should call a realtor. When people realize what’s going on at the coast, land’s going to get really expensive.’ ”

Jordan got a deal on 43 acres from “a couple of pot farmers.” He put in his vineyard, fencing the land, developing a spring and building a small, solar-powered cabin. The vineyard, which grows Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Syrah, consists of 11 acres.

“I can always tell my wines in a blind tasting,” Jordan says. “They have an acid-tannin tension that’s fascinating.”

The reds, in particular, seem to echo the region’s haunting loneliness. They possess a wild, woodland quality.

Del Dotto Vineyards

Former TV infomercial personality Dave Del Dotto had produced Rutherford Cabernet Sauvignon since 1993. But in 2006, a bottle of W.H. Smith’s Maritime Vineyard Pinot Noir enjoyed at Bouchon, the Yountville restaurant, changed his perspective.

Former TV infomercial personality Dave Del Dotto had produced Rutherford Cabernet Sauvignon since 1993. But in 2006, a bottle of W.H. Smith’s Maritime Vineyard Pinot Noir enjoyed at Bouchon, the Yountville restaurant, changed his perspective.

“I thought it rivaled Romanée-Conti,” Del Dotto, 62, says. He eventually met Smith, “who told me he wanted to sell the property. I bought it instantly.” He renamed it Cinghiale, which means “wild boar” in Italian.

The vineyard sits 1,800 feet above sea level and consists of 42 acres. Yields are tiny, which Del Dotto attributes to the scarcity of water and the gravelly dirt.

“It’s like a quarry up there,” he says. “I don’t even know how the vines live.”

Flowers Vineyard & Winery

Flowers Vineyard & Winery

Walt and Joan Flowers purchased their Camp Meeting Ridge property in 1989.

“Hirsch was there, and the old Bohan place, but not much else,” says Jason Jardine, president and director of winemaking under Flowers’ new ownership, the Huneeus family (of Napa Valley’s Quintessa).

“The Flowers took a tremendous risk,” Jardine says. “People told them, ‘Don’t do it, it’s too wet, too cold.’ ” But the couple had owned a successful nursery.

“They understood weather and soils,” Jardine says, “so they bought 327 acres and planted their first grapes in 1991.”

A second purchase, in 1998, at a higher ridge Jardine calls Sea View, brought the area under vine to 42 acres, which makes Flowers one of the area’s biggest growers. Elevations range from 1,150–1,900 feet above sea level, while annual production averages about 3,000 cases of estate Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Fort Ross Vineyard

Fort Ross Vineyard

Linda and Lester Schwartz emigrated to the U.S. from South Africa in 1976.

“Politics made us do it,” Linda says. “We felt that by living in that [apartheid] society, one was condoning it. Lester always longed for land.”

One day, while exploring the coast near Fort Ross, they drove up to the ridge top and looked down.

“Lester nearly swooned,” Linda says. “He could not believe the beauty of it all.”

They bought 970 acres, 50 of which are now planted to grapes, including Pinotage, which was originally developed in South Africa.

At elevations of 1,200–1,700 feet, Linda says the vineyard “is in the sun, surrounded by fog lower down, nipping at the edges.”

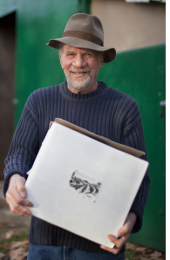

Hirsch Vineyards

Hirsch Vineyards

David Hirsch’s 1978 arrival in Fort Ross was “by accident,” he says. In the decade that followed, he had “a hobby vineyard,” but it wasn’t until 1990 that he took to grape growing full time. Planted acreage now totals 68 acres, mainly Pinot Noir.

In 2002, Hirsch launched his own eponymous label, but about half the grapes still are sold to other wineries, including Williams Selyem, Siduri, Failla and Littorai.

Like many of his neighbors, including the Martinellis and the Nobles Vineyard (which sells Pinot Noir to Schramsberg and Morlet Family), Hirsch sold grapes to Kendall-Jackson in the early 1990s. K-J’s role in aiding the region’s pioneers has never been fully appreciated.

Martinelli Winery

Few names are as tied to the Fort Ross area as the Martinellis and their relatives, the Charleses, whose roots in the hills go back to the 1850s.

Lee Martinelli Jr., says his grandfather, George Charles, planted Chardonnay in 1981. “It had tonnage, people were seeking it out and he needed a variety that got ripe early.”

Lee and his father first planted Pinot Noir in 1995. They began producing wine under the family name around the same time.

The Martinellis have watched the land rush to their area in wonderment.

“I feel fortunate that my ancestors have a lot of history there,” Lee says. “People are stumbling to buy their way in now—a contrast to my grandfather. When he was first putting in grapes, he actually used a horse. To see now these people clamoring in with their Lexus SUVs, well, it’s just amazing.”

Pahlmeyer

Pahlmeyer

Lawyer-turned-vintner Jayson Pahlmeyer had already achieved acclaim for his Napa Valley wines when he turned to Fort Ross, Here, he believed he could craft, “French Burgundy, the Holy Grail. That’s what I’m chasing!”

He named the land he bought in 2000 Wayfarer Farm Vineyard. “It had been owned by hippies whose first crop was something you’d smoke,” he says. “They called it ‘Wayfarer’ because they’d turned it into a school for wayward kids.

“The real problem up here is, there’s no water,” Pahlmeyer says. He eventually got permission to build a reservoir, which provides just enough water to support 30 acres of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Precious Mountain Vineyard

Precious Mountain Vineyard

Donnie Schatzberg is a grower who’s chosen not to produce wine, instead selling his grapes exclusively to Williams Selyem. Even after 40 years, Schatzberg says, “I feel we never left those early days of building my house and homesteading.”

Among Pinotphiles, the six-acre Precious Mountain Vineyard is highly esteemed, frequently producing one of Williams Selyem’s best wines. The vineyard is on the second ridge in from the ocean, one locals call Creighton.

Schatzberg calls it a “marginal area, in terms of bringing grapes to ripeness, but we’ve never come up short on sugar,” even in such cool years as 2011. The vineyard is dry-farmed out of necessity.

“The reality is, I don’t have the water,” he says

Wild Hog Vineyard

Wild Hog Vineyard

Daniel Schoenfeld “did a bunch of different things” before stumbling across his Fort Ross land in 1973. To survive, he had a heavy equipment business. On the side, he was learning about wine.

“I got some Cabernet about that time, I think from Sterling, and decided to make some wine,” Schoenfeld says. “We bought a book and followed our instincts, but we were amazingly ignorant.”

In 1981, he planted Zinfandel and Gewürztraminer. Later, he budded the Gewürz over to Pinot Noir, but retained the Zinfandel because, “we’re on the southwest-facing slope of the third ridge in, and it’s a lot warmer than the first two ridges.”

Schoenfeld admits to mixed feelings about growth. “I’m not wild about change,” he says. “A lot of the new people who came in with millions of dollars tended to not become part of the community. But all of us are really proud of our new appellation.”

Mohrhardt Ridge Vineyard

Phil Mohrhardt sells his grapes exclusively to Wellington Vineyards. But he’s integral to the history of Fort Ross, and many refer to the ridge where his vineyard is located as “Mohrhardt Ridge.”

He planted his first grapes in 1984, “before anyone else,” starting with five acres of Cabernet Sauvignon. Why the great grape of Bordeaux in a region now definitively Burgundian? “That’s what the advisor from the junior college recommended,” Mohrhardt says.

Wellington has purchased the grapes since 1989, and it crafts an affordable Cabernet that’s grippy and tannic when young, but ages well.

The ranch, which covers 2,200 acres, extends up to 2,300 feet above sea level, “and is steep, rugged and forested,” Mohrhardt says. Would he ever plant Pinot Noir?

“We’ve thought about it,” he says, “but even with all that acreage, there’s not a lot of land that’s suitable.”

Top-Scoring Wines

98 Williams Selyem 2010 Precious Mountain Vineyard Pinot Noir (Sonoma Coast). Cellar Selection.

abv: 14.3% Price: $75

98 Flowers 2010 Sea View Ridge Estate Vineyard Pinot Noir (Sonoma Coast).

abv: 14% Price: $70

97 Failla 2010 Hirsch Vineyard Pinot Noir (Sonoma Coast). Editors’ Choice.

abv: 13.9% Price: $65

95 Fort Ross 2010 Fort Ross Vineyard Sea Slopes Pinot Noir (Sonoma Coast). Editors’ Choice.

abv: 14.5% Price: $36

94 Hirsch 2010 East Ridge Estate Vineyard Pinot Noir (Sonoma Coast). Cellar Selection.

abv: 13% Price: $85

93 Del Dotto 2010 Cinghiale Vineyard Reserve Chardonnay (Sonoma Coast).

abv: NA Price: $125

93 Martinelli 2009 Three Sisters Vineyard Sea Ridge Meadow Chardonnay (Sonoma Coast).

abv: 14.1% Price: $60

90 Wild Hog 2009 Pinot Noir (Sonoma Coast). Cellar Selection.

abv: 14.5% Price: $30